African Cybercrime: A criminological theory and geopolitical analysis of INTERPOLs Operation Serengeti 2.0

By Lucius Tuck

“According to the World Economic Forum, cybercrime has reached such alarming levels that it is now considered the third-largest economy in the world, following the United States and China. This illicit sector generates more revenue than the combined global markets for illegal drugs, counterfeiting, and human trafficking.”

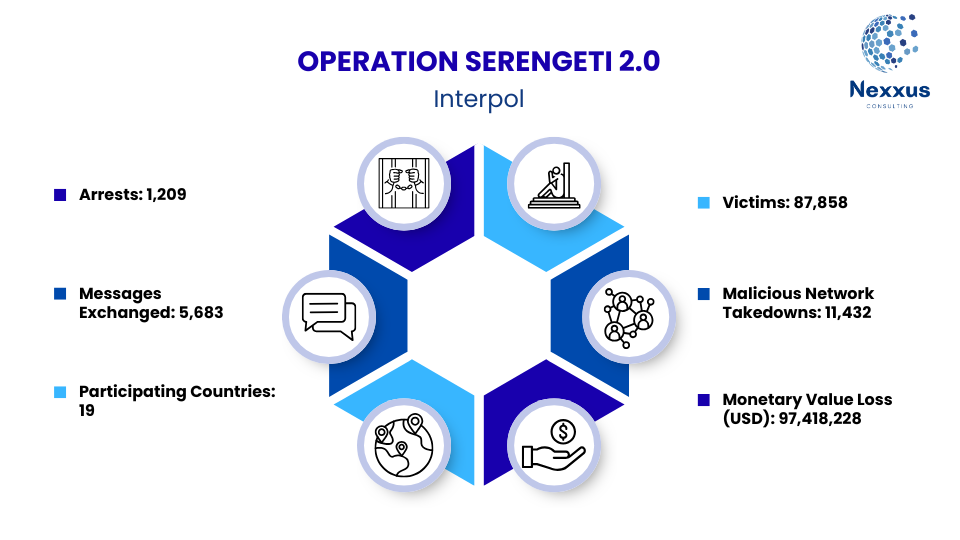

On August 22nd, 2025, INTERPOL announced the conclusion of a massive multi-nation, multi-agency operation which sought to address the scourge of cybercrime spreading across the continent of Africa. Now known as “Operation Serengeti 2.0”, this three month, nearly continent-wide effort to tackle the growing crisis of cyber-criminality in Africa has yielded considerable results. According to INTERPOL, Operation Serengeti 2.0 resulted in the arrest of “…1,209 cybercriminals targeting nearly 88,000 victims. The crackdown recovered USD 97.4 million and dismantled 11,432 malicious infrastructures”. This operation was made possible by cooperation and coordination between 18 African countries, the United Kingdom, multiple agencies within each of those countries, and numerous private sector entities with specializations in finance, communications, technology, intelligence, and security from around the globe.

What we learn from Operation Serengeti 2.0 is just how crucial international law enforcement coordination is to combatting cybercrime. This operation could not have happened without the willing cooperation of law enforcement agencies from multiple countries, working in tandem and sharing information with each other, as well as support from the private sector through intelligence collection, training, and guidance for local law enforcement. According to the Secretary General of INTERPOL: “Each INTERPOL-coordinated operation builds on the last, deepening cooperation, increasing information sharing and developing investigative skills across member countries. With more contributions and shared expertise, the results keep growing in scale and impact.”. The success of Operation Serengeti 2.0 has bolstered this statement as it will likely prove to be a valuable model for future efforts to stop cybercrimes in other regions because Africa is an informative case study for how these types of networks work across borders and how law enforcement must respond in kind to such activity. Africa is such a particularly interesting example to learn from for multiple reasons. Besides Africa making up a total of 54 sovereign nations each with unique cultures and multiple languages, spread across the largest landmass in the world, this continent continues to bear the scars of its colonial legacies resulting in acute poverty, limited resources, and political turmoil.

A useful example of the cross-border migration of cybercriminal networks is the case of Nigeria and Ghana, where Nigerian cybercriminals easily transferred their operations to Ghana when regulators, legislation, and law enforcement attention began to hamper their efforts. This is exemplary of the cybercrime landscape that law enforcement around the world is dealing with today. Not only can cybercriminal networks quickly transport their operations across borders when they get nervous, but cybercrime networks can operate from anywhere in the world, conducting operations anywhere else in the world. “Cybercrime may be committed without the physical presence of the perpetrator at the place and time of commission of the crime and co-perpetrators can even communicate online without knowing each other. Moreover, perpetrators can commit thousands of crimes against thousands of victims within a short time”. At the same time, technological advances and the growing ubiquity of access to new technologies has created an environment where the threshold to accessibility for such resources that facilitate cyber-criminality has been lowered to such an extent that nearly anyone with the will to commit cybercrime now has the ability to do so. “…with the dark web and AI enhanced tools, it means that any individual may obtain the necessary skills and software to develop new attacking strategies”. So considering that the barrier to entry has been lowered so that nearly anyone can commit cybercrimes, and cybercrimes can be committed entirely remotely, from essentially anywhere to anywhere else in the world, why is Africa such a hotbed of cyber-criminality? Several criminological theories have been employed to attempt to explain the unique intensity in the growth of cybercrime in Africa as compared to other regions. There are also broader theories, that incorporate geopolitical and historical realities that could bring insight to the African cybercrime phenomenon.

Applying Criminological Theories

Anomie Theory

Anomie theory was first developed by Robert K. Merton and inspired by Emile Durkheim’s concept of “a social condition in which institutionalized norms lost their power to regulate human needs and action”. This nearly century-old criminological theory applied in relation to cybercrime has been adapted to suggest that, “anomie theory proposes that the fast-paced technological advancements and the absence of well-defined regulations regarding online conduct fuel the spread of cybercrime”. This interpretation implies that the exponential growth of public access to technology and persistent technological improvement have so significantly outpaced the law enforcement, legal, and regulatory capacity to defend against, and more importantly, educate populations to understand and care about the societal repercussions of cybercrime, that most people do not grasp the greater social impact that cyber-criminality can have on them and culture at large. This cybercriminal anomie theory could certainly play a role in the rapid growth and apparent acceptance of cybercrime in Africa, but it does not address underlying issues. It simply offers a reason for the problem without opening the door to many possible solutions to it.

Differential Association Theory

Differential Association theory is another criminological theory that has been presented to grapple with the causes of the persistent expansion of African cybercrime. Originally, and still most commonly utilized to examine affluent, white-collar crime, differential association theory posits that those who develop “…association with definitions favorable to violation of law eventually shapes their orientations and transforms them from white-collar workers into white collar criminals”. Essentially, if the culture you are a part of becomes comfortable with, and increasingly prone to criminal behaviors, your association with such behavior shapes your own concept of legality and your own moral compass related to such forms of criminality. “In the context of cybercrime, [differential association] theory suggests that young individuals who are exposed to peers engaging in cybercrime are more likely to engage in such behavior themselves. Furthermore, the theory proposes that individuals who possess advanced knowledge in science and technology may be more prone to committing cybercrime”. This theory is supported by studies like the 2019 research by Ogunley et. al. which focused on an increasing number of female undergraduate students in Nigerian universities who were committing cybercrimes. As the theory suggests, the study found that this was learned collective behavior, introduced by peers in the university setting. While this certainly bolsters the validity of the theory as being relevant to some particular instances of criminal activity, it doesn’t relate to a majority of the cybercrime committed on the continent, merely some unique, particular examples. Similar to the application of anomie theory, this theory offers opportunities to place blame on a group and a social phenomenon without adequate avenues for how this theory’s conclusions could provide solutions. This application of differential association theory suggests that the blame for increasing cybercrime in Africa should be placed on particularly adept and capable youth with advanced practical skills. Any solution that could be drawn from such a theoretical conclusion would lead to law enforcement targeting the most highly educated and particularly, the best STEM students in Africa. This is clearly not a viable or beneficial solution for the continent of Africa.

Neutralization Theory

While there is certainly something to be learned from the application of anomie theory, considering that the conclusion it leads to relates to widespread poverty being a source, pursuing this theory without greater context would limit the extent to which the problem is truly addressed. At the root of both theories is the fact that, “…poverty and underdevelopment are the primary causes of the growth of cybercrime in the region…”. Another criminological theory that can be applied to the rise of African cybercrime – and may provide a better sense of root causes – is Neutralization theory. This theory, established by Gresham Sykes and David Matza, suggests that criminals use rationalization and justification techniques to diffuse culpability from themselves and relieve themselves from any guilt associated with their criminal activity. “In the context of cybercrime syndicates, these rationalizations enable scammers to view their victims as deserving of exploitation, often based on assumptions about their wealth or social status. By framing their crimes as economically driven or as acts of retribution against perceived societal inequalities, fraudsters detach themselves from the moral consequences of their actions”. Neutralization theory, in this case, allows for a deeper investigation into the reasons behind the increase in cybercrime throughout Africa. Unlike the previous theories, neutralization theory applied to this case does not place blame on a specific group of people (like differential association appears to target tech-savvy youth seeking an education,) nor does it blame the issue on the governments and institutions of African countries for not developing cyber defenses fast enough to keep up with cybercriminals, like anomie theory seems to. In the case of African cybercrime, using the basis of neutralization theory allows for a more nuanced discussion about why African cybercrime is so rampant and what can be done about it.

Historical Legacies

Applying neutralization theory to cybercrime in Africa provides us the opportunity to understand why the neutralization techniques are so easily employed by criminals in this setting. “Colonialism left behind a legacy of exploitation, economic disparity, and institutional underdevelopment, creating long-standing grievances that continue to shape contemporary realities. In regions that experienced extensive colonial rule, systemic poverty, limited access to education, and weakened governance structures have created an environment where cybercrime can flourish ”. The legacies of colonial rule by European countries across the African continent and the continued marginalization of African nations in international economics and geopolitical decision making have left Africa vulnerable to the spread of cybercrime, and have left the citizens of African nations with more than a bad impression of the nations that ravaged their continent and have since neglected to repair the damage they caused. Consequently, it is no wonder that many citizens of African nations do not have much sympathy for the considerably more affluent citizens of the US, for example. Considering this context, the employment of neutralization techniques that alleviate feelings of guilt associated with committing fraud scams against individuals, or ransomware attacks against corporations in affluent countries that once colonized African lands is not difficult to understand. It also explains why China and Russia have had greater success at becoming involved in infrastructure and security projects in African countries in recent years, since they do not directly bear the stain of being former colonizers. Understanding the reasons behind the rationalizations used to diffuse guilt from cybercriminals targeting citizens of Western nations allows for more frank discussions about why Africa is seeing so much cybercriminal activity.

Simply being aware of this context does not immediately suggest a solution, but it allows for a more productive discussion about root causes, while also emphasizing how interconnected the global cyber-landscape is and how inextricable from geopolitics this discussion of cybercrime truly is. As has been mentioned, a considerable number of the cyber-attacks coming out of Africa target citizens of Europe and the US. Irrespective of the historical grievances that were mentioned in relation to neutralization techniques, this is largely due to the considerably greater affluence of these countries. It is more lucrative to target European and US citizens because the economies of those countries are much stronger and thus there is a much lower rate of poverty. While African cyber-criminals also certainly attack citizens and corporations within the African continent, causing devastating effects on supply chains and critical infrastructure as well as small-scale scams targeting African citizens, it is much more profitable to target those in wealthier countries. This dynamic is critical to point out because the effort to stem the tide of African cybercrime is not the responsibility or prerogative of African nations alone, it is necessarily a global effort, both from the perspective of collective solidarity as well as self-interested national security and sovereignty.

Sovereignty & International Cooperation

“Cyber sovereignty… refers to a state’s ability to exercise control over its own digital infrastructure, data, and cyber policies without external interference… However, maintaining cyber sovereignty requires not only domestic legal measures but also stronger international cooperation”. INTERPOLs coordination with African nations across multiple operations conducted recently including Operation Serengeti, Operation Red Card, and now Operation Serengeti 2.0 are a step toward both cyber-sovereignty for African nations as well as a greater cohesion among law enforcement and intelligence agencies from countries around the world. The more that countries invest in intelligence sharing and law enforcement training in cooperation with organizations like INTERPOL and regional institutions, the better INTERPOL and the global community can respond and be aware of what is necessary to defend against and crack down on cyber criminals worldwide. Africa may be particularly vulnerable to the proliferation of cybercrime networks and syndicates, but this is not an African problem. This is undeniably a global problem, and it must be addressed with collective global solutions.

References:

- Adewopo, V.A. et al. (2025, June 12). “Comprehensive analytical review of cybercrime and cyber policy in West Africa”. Journal of Electrical Systems and Inf Technol 12, 20 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43067-025-00216-x

- Azam, B. & Musah, M. (2025). Colonial Injustice and Cybercrime: The Role of Historical Grievances in Fraud Justification. 10.13140/RG.2.2.17092.33920.

- The Hacker News. (2025, August 22). INTERPOL arrests 1,209 cybercriminals across 18 African nations in global crackdown. https://thehackernews.com/2025/08/interpol-arrests-1209-cybercriminals.html

- Henrico, S. & Els, S. (22 Apr 2025): Cyber Attacks in South Africa: Geopolitical and legal implications, African Security Review, DOI: 10.1080/10246029.2025.2489352

- INTERPOL. (2025, August 22). African authorities dismantle massive cybercrime and fraud networks, recover millions. https://www.interpol.int/News-and-Events/News/2025/African-authorities-dismantle-massive-cybercrime-and-fraud-networks-recover-millions

- INTERPOL. (2025a, March 24). More than 300 arrests as African countries clamp down on cyber threats. https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2025/More-than-300-arrests-as-African-countries-clamp-down-on-cyber-threats

- Kaspersky. (2025, March 24). Kaspersky supports INTERPOL-led operation Red Card, resulting in over 300 arrests. https://www.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/kaspersky-supports-interpol-led-operation-red-card-resulting-in-over-300-arrests

- Lilly, Cullen, F. T., & Ball, R. A. (2019). Criminological Theory: Context and Consequences (Seventh edition.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Mpuru, L. & Kgoale, C. (16 Jun 2025): Recognizing the Evolving Cybercrime Threats in South Africa, African Security, DOI: 10.1080/19392206.2025.2515302

- Ogunleye, Ojedokun, & Aderinto. (2020). Pathways and Motivations for Cyber Fraud Involvement among Female Undergraduates of Selected Universities in South-West Nigeria. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3702333

- Rahman, Asia & Ali, Salman. (2025). The Role of Neutralization Techniques in Fraud Migration: Cybercrime Syndicates in West Africa. 10.13140/RG.2.2.28207.24489.

- Sasipornkarn, E. (2025, August 22). Interpol arrests over 1,200 in African cybercrime crackdown. dw.com. https://www.dw.com/en/interpol-arrests-over-1200-in-african-cybercrime-crackdown/a-73736645

- Umer, Fahad & Rahman, Nadia. (2025). Fraud Migration and the Expansion of Cybercrime Networks: A Nigeria-Ghana Case Study. 10.13140/RG.2.2.26008.51202.